[in

italiano]

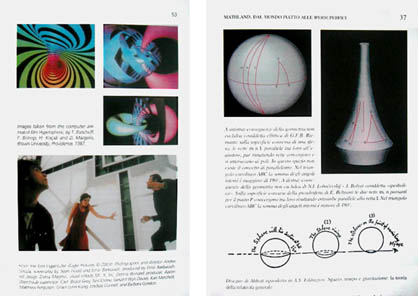

> IT REVOLUTION BOOK SERIES

|

|

Michele

Emmer deals with several absolutely crucial arguments in this volume.

To recall them in order: a. space does not exist as an objective fact

but simply as a mental (and scientific) form; b. these mental and

scientific forms of representing space vary from era to era (for example

flat Euclidean space, three-dimensional Cartesian space, Gauss' curvilinear

geometry, Riemann's 'n-dimensional' geometry, etc.); c. these mental

and scientific forms have utilitarian value. We use them if they work,

we set them aside if they do not work. Euclidean geometry is more

than accurate when dividing up farmland but we must come up with another

one to measure the curvature of solar rays. (At times, the truth is

mathematicians first invent the scientific theory and then later,

occasionally much later, discover the physical phenomena to which

it could usefully be applied); d. these mental forms in any case have,

or can have, intrinsic beauty. This aspect of beauty cannot be ignored

because otherwise we could not explain either the total immersion

the work of the mathematician requires, or the intimate familiarity

between mathematician and architecture: even though from different

angles, they are both polysemic disciplines, they serve a practical

end, but they neither exhaust themselves nor become flat on this.

Setting aside the exceptional competency of the author, these arguments

are illustrated in Mathland with two rare qualities: first

of all, with exemplary clarity and secondly through a controlled,

subterranean passion that is still however transmitted to the reader.

I believe many, after the first reading, will want to return to the

pages to make drawings and notes, to attempt to read more on the same

material by the same scholar. I am also convinced that if this book

falls into the hands of an intelligent high school student or a student

of architecture or engineering that it would be a good way of understanding

the great framework in which to apply the necessary hard work of mathematics.

But naturally Mathland has even greater importance as part

of this book series for architects and researchers who give center

place to the relationship between computer technology, new scientific

discoveries and the central problem of architects: space. Emmer writes:

I would like to recount just a small part of the story that led to

profound changes in our idea of the space that surrounds us, and help

understand how in some sense we ourselves create and invent space,

modifying it according to changes in our ideas of the universe. Or

perhaps one could say it is the universe that is modified following

the mutations in our theories. The word mutation, the word transformation

are the keys to this understanding.

Space, as shown in this book, "mutates" and is strictly dependent

on our scientific concepts. The concept of mutation of these scientific

concepts is important because even architecture mutates over time

with the various periods and variations in the tools that allow its

realization. Now, we maintain the fundamental tools that give form

to architecture are not only materials, construction techniques and

functions but above all spatial and scientific concepts. As if mathematical,

geometric and scientific knowledge of space is transformed into physical

construction, into "things" through architecture. Look for example

at the Egyptian Pyramid. Is not the Pyramid (and I have already discussed

this theme in this series) the edification of several notions of geometry

and trigonometry? Indeed, without those notions, without those mental

forms, would the Pyramid even be conceivable? Is not the Pantheon

the fruit of a very sophisticated geometric calculation, of considering

space and calculations under the form of a "geometry" evidently possessed

by the Romans (who would have never been able to construct that type

of edifice with their abstruse numbers). And let us make the example

of all examples with the affirmation of a new architecture at the

beginning of the 15th century. Was not the invention of perspective

perhaps at the basis of the transformation of the architecture of

Humanism? Perspective became 'reified'. Indeed, the scientific concept

is precisely what finally makes space perceptibly "measurable" and

leads us to consider an architecture made in its image and likeness:

a modular, proportioned architecture, made up of repeatable elements

made to be "perspectiveable".

We can be certain of some of these relationships between the scientific

concepts of space and architecture, the relationship between perspective,

the architecture of Humanism and the Ptolemaic universe, or that of

Cartesian space, of the Mongian projection system and the progressive

birth of an architecture first a-perspective and then more and more

abstract and analytical. But what is happening today? Where are we

going? Because if the concept of space has been mutated (and how it

has!) and if the computer technology of this mutation is an agent

to at least two or three different powers, then we are in a field

of research as rich as it is difficult.

To understand some of these territories and attitudes, it would be

useful to recall one point that moves throughout this book. This is

the figure of the leap or rather the act of the leap. Emmer explains

that in order to understand a space one cannot be immersed in it but

must make a leap outside it. Remember? In another circumstance we

spoke of fish: fish only know fluid as if it were air around them.

They know nothing either of what the sea or a lake or a river might

really be and know even less the space in which humans live. Only

a "leap" outside that aquatic surface can open up the sensation of

another space.

Now this book has made an indispensable contribution and enriched

research into new spaces. We begin to understand the laws and see

several possibilities. Above all we are in a "topological" concept

of space (we are not interested in the construction of geometric "absolutes"

but in systems of families and possible relationships between forms)

and are also working to give form in architecture and spaces actually

explorable in more dimensions with respect to the three Cartesian

ones, dimensions in which the space-time geometry is actually something

different than what we have been accustomed to since Newton. How to

do that? How to imagine these spaces that are "absolutely" just as

real as those we are traditionally accustomed to considering? In reading

this book, you will see that asking these questions will seem natural

to you as well. Welcome to Mathland and just like dolphins

that take oxygen to leap out of the sea or like Abbott's Square

suddenly catapulted into three dimensions, you will think as well:

"An unspeakable horror seized me. There was a darkness; then a

dizzy, sickening sensation of sight that was not like seeing; I saw

a Line that was no Line; Space that was not Space: I was myself, and

not myself. [...] Either this is madness or it is Hell." But anguish

quickly gave way to wonder: "A new world!"

Antonino Saggio

|

|

[20dec2003] |