|

|

| home > files |

| Dublin

conversation Elena Carlini and Pietro Valle |

| Elena

Carlini and Pietro Valle talk to Sheila O'Donnell and John Tuomey. |

||||

| [in italiano] | In

the world of media-obsessed contemporary architecture, the work of Irish

designers Sheila O'Donnell and John Tuomey constitutes an act of resistance

against facile consumptionism. In the last 15 years, the two have completed

a large number of public structures redefining contemporary Irish architecture

as a responsible practice able to address diverse contexts with design

rigor and poetic inventiveness. O'Donnell and Tuomey, after studying

in Dublin in the 1970s, went to work in London for James Stirling. In

England, not only did they absorb his eclectic collage technique but

also current trends in urban analysis present in the continental rationalist

schools. Back to Ireland, they tried to insert this European vision

into the then stagnant local scene. They worked collaboratively on a

number of urban schemes during the 1980s and ended up establishing Group

91 with other ten practices at the beginning of the last decade. The

joint venture proposed a comprehensive urban redevelopment plan for

the then derelict Temple Bar District in the center of Dublin. Their

scheme was luckily accepted by the government as a sensible proposal

for the preservation of the urban morphology and, in the subsequent

ten years, the neighborhood was gradually transformed, becoming a huge

public success. In Temple Bar, O'Donnell and Tuomey built important

cultural structures such the Irish Film Center, the National Photography

Center and the Photography Archives, all sensible contemporary additions

to the existing fabric of the area. Since then, the duo has completed

a number of structures including schools, public housing schemes, a

golf center and many private residences. They are currently designing

two new projects in the Netherlands: a multi use complex and a school. O'Donnell and Tuomey's architecture is characterized by material and spatial diversity related to a careful reading of the different places where their projects are located. The two architects react to the isolated condition of Ireland, historically dominated by other cultures, with an incredible sensitivity that absorbs influences from abroad and is also in harmony with the nature of the individual context. This combination of influences has also enabled them to address the meaning of many public institutions inherited from the British rule or from the Roman Catholic Church, reorienting them towards a contemporary collective use. In this light, we can read the three recent educational projects presented here. The Ranelagh Multidenominational School is a primary facility located in a historic district in Dublin near the Georgian development of Mountpleasant Square. The new building responds to the existing street scale by breaking into multiple brick 'houses' while at the back it is unified by a light wood pergola and loggia. The Furniture College in Letterfrack in the west of Ireland transforms an existing Victorian campus into a new a technical school. O'Donnell and Tuomey's master plan has changed the approach to the whole complex by turning the existing symmetrical approach into a gradual curved one along which the visitors encounter an array of different structures. So far, the wooden workshops have been built, huge 'tilted barns' in the wind, but next will come a library, as well as administration and public facilities. The Art Gallery and Restaurant for University College Cork, which started construction recently, is an individual pavilion. A plinth links the new structure to an existing limestone escarpment that surrounds the entire hillside on which the campus is located. From it springs a light wooden structure suspended among the treetops and offering views on the nearby river. This floating 'vessel' is composed of a series of elegantly interlocking spaces that gradually ascend from the common stone ground. PIETRO VALLE: What elements do you take into consideration when you design buildings? JOHN TUOMEY: We are very involved with the idea of the connection to place. We are not thinking of our buildings as solving immediate needs or addressing functional requirements. We, instead, consider them as readings of an existing context. SHEILA O'DONNELL: We increasingly identify the character of a place through a combination of different elements such as the physical, the social, the aesthetic and the material. We try to avoid establishing direct links to historical or traditional architecture. We could distill a reading of the tradition of a place but we never quote it directly. We try instead to discover what is important to us in a location and what can be conveyed in a contemporary situation. |

[21mar2003] | ||

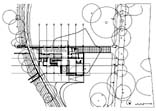

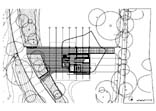

Ranelagh Multidenominational School, Dublin. Site plan.  Playground view.  Classroom block.  Classroom. |

|

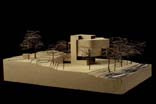

Ranelagh Multidenominational School, Dublin. Plan.  Model. |

||

| JOHN

TUOMEY: I think, though, that it is very important to distinguish our

position from a conservation minded one. We engage history as a living

cultural presence. The trouble with the current division of the world

between conservationists and modernists is that it blocks creative contact

between those things that are actual, whether they are old or new. If

you consider the entirety of what exists in the living present then

there is the possibility to be radical within that continuity. We find

that we can make contact with other innovative projects even if they

are historic projects: they do not have to be contemporary. In our work,

we are less concerned with up to date appearances or direct historic

links but rather try to feel that the physique of what we are making

is fitting with the physique of what exists even if that sometimes involves

an opposition. PIETRO VALLE: Let's talk about your relation to Ireland. This country has at least two unique elements. One is the radical social and economic change that has occurred in the last ten years, the other is the fact that others have always owned Ireland's history and therefore people do not feel particularly attached to an urban environment that was imported from Britain. How do your respond to these two elements? How do they inform your responsibility to place? SHEILA O'DONNELL: In Dublin, the most important buildings and the urban fabric are still seen as being imposed from the outside but we think that, even if they were built by the British, the environment is very different from England. Dublin is physically distant from London even if both cities have large parts built in the Georgian period. I do not ultimately think that this alien tradition is a critical element in our appreciation of the place. JOHN TUOMEY: We are not post-colonial. Our parents' generation was post-colonial: they did not recognize that the things around them belonged to them. They stated no claim to the place. The major monuments of Dublin were neglected in the period after the independence of Ireland because people felt a distance between them and the meanings of those monuments. Dublin Castle, which is the centre of the city, had been ignored for generations because people identified it with British rule. Any organized urban set piece was regarded as imported or transplanted. However, by the time we came along, we had a different perception of the persistence of monuments as opposed to their literal historical meaning. We thought of them as a continuous background against which we lived our lives. We did not have the dilemma of making ourselves exist in opposition to something that was conditioning us. We had greater freedom and our instinct was to look towards Europe. I think that would be a way to define our generation in Irish architecture: we looked towards Europe for direction. We graduated in 1976 and this was at the time when Aldo Rossi's "The Architecture of the City" was translated in English. It was a book that was very influential on our thinking because someone was actually talking a language that we could understand, the language of the continuity of the European city. In addition, we did not feel a strong cultural tie to America because, unlike the previous generation of Irish architects, we were fundamentally British educated and trained. This contact with England was surely a privilege but we also felt it was not going to define us completely. Therefore, we incorporated ideas from the school of urban analysis and took the task of re-imagining Dublin as a European city. We also extended our search to the buildings in the landscape trying to understand them as part of a larger metropolitan project. SHEILA O'DONNELL: We stayed in London for 5 years after graduating in Dublin. Living in England, coming back to visit and finally settling here made us aware of how physically different England and Ireland really are. Before leaving, we thought that the cities and even the buildings in the landscape were similar but distance made us aware of the unique way structures are sited and made here. |

||||

Furniture College, Letterfrack. View from North.  Machine hall interior. |

O’Donnell + Tuomey. Furniture College, Letterfrack, Ireland 2001. Furniture restoration units. PIETRO VALLE: To what degree this awareness of the Irish environment has influenced your work? JOHN TUOMEY: I am not sure we are trying to define a kind of 'Irishness' in architecture. Our position has developed from being defensive, to a larger appreciation of diversity. In comparison to our European colleagues, we did not have a tradition or a legacy to respect. We rather saw that our role was to introduce a contemporary architectural culture into Ireland. We were not reacting against an existing establishment, we were trying to lay the foundation for a new way of seeing and this made us, at the beginning, quite rigorous about what our design freedom was. In our initial work of the early 80s, we were trying to lay down general principles with which architecture could be practiced both in the Irish environment and in general. This was influenced by established trends of urban analysis present at the time in European architecture. |

Furniture College, Letterfrack. Under Diamond Hill.  Entrance approach. |

||

| SHEILA

O'DONNELL: At the beginning we were trying to work out what was particular

about Ireland but, as John was saying, it was an excuse to introduce

design rigor and analytical capacity. We felt that, historically, buildings

here had a more stark contrast with the landscape, being almost prismatic

in form while in England they tended to soften their presence with informality

and picturesqueness. After coming back from London, we spent a number

of years exploring the country and observing how things were made. We

did work which was like a study of the place and we now feel that this

helped us enormously to absorb it. Nowadays we rely more on intuition

to judge how we put things in the landscape whereas then, in the early

80s, we were always trying to verify some specific analysis of how things

were done in the past. JOHN TUOMEY: I still think, though, that we are not very liberal. Our work is typologically rooted and we still need to feel that there is a rational basis for the diagrams of our projects. That is what formed us but that is not what we are pursuing. Even within that rigour, we are now searching for something that is much more evocative, that has a psychological resonance or even an emotional point of contact. ELENA CARLINI: What about your current experience of working in the Netherlands? SHEILA O'DONNELL: We are doing two projects in the Netherlands: one, a mixed-use development in Delft, is quite urban and set in an old city built in the 15th and 16th century. We were very impressed by the material quality of Delft and then there is a story that relates it to Dublin. Dublin is built with bricks that are quite different from London's: they are actually Dutch bricks that were brought over to Ireland as ballast. When the English were shipping away all the riches from the country, they needed something to give back. They brought Dutch brick to Ireland and Georgian Dublin was all built with it. It is interesting that our first project in Holland was an urban project. We could respond quite closely to the materiality and scale of Delft. In addition, there was a sense of urban continuity that does not exist in Dublin. JOHN TUOMEY: The architecture we enjoyed in Delft goes beyond hierarchy. Holland is the land of everyman: all the houses, even the fine houses, have this thing in common, that class does not divide them. There is not the duality of the palazzo versus the cottage. We found this plainness, this unpretentiousness, very refreshing. However, at the same time, we have suffered for not having being able to adapt to a country that believes so strongly in systems. The whole of Holland is a functional platform. Even the landscape is man-made and artificial: it is hugely complex in the way it challenges nature but, at the same time, it is deeply simple in the sense that things do not have layers there, they are just solutions. We have a hard time with the idea of a system becoming reality. We are much better able to deal with entanglement than with straightforwardness. ELENA CARLINI: You always expect to find layers of complexity but there are not any over there. JOHN TUOMEY: I think it is a problem. Poetics or mystery are not abstract concepts to us, they are survival strategies to deal with everyday life. In Holland, they are not common ground and so we find we are a little bit romantic when compared to the Dutch. We would not have imagined this difference before starting these jobs. |

Furniture College, Letterfrack. Section model.  Concept sketch. |

|||

Art Gallery and Restaurant, University College Cork. River view.  Model. |

O'Donnell + Tuomey. Art Gallery and Restaurant, University College Cork, Ireland 2002-2004 (under construction). Campus view. PIETRO VALLE: This is an interesting issue: the reaction to another culture polarizes your being tied to a specific local approach. JOHN TUOMEY: This is not completely true. We recently went to Japan to take part to an exhibition of recent European architecture. You think that Japan is the most remote country a European could ever visit but we both felt, instinctively, that there were things we could never penetrate, that there were mysteries. This made us feel much more at home in Japan than we could ever feel on the plains of Holland. SHEILA O'DONNELL: We were intrigued by the fact that Japan has changed so much. Tokyo has amazing contemporary buildings whose life span is expected to be 25 years because land values are so much higher than building values and therefore the place has to be continuously redeveloped. At the same time, the Japanese have managed to combine a fantastic level of change with a strong sense of cultural continuity. This co-presence has layers and you are quite amazed to find that, beyond appearances, Japanese culture has survived quite intact and there is not as much concession to the West as one might expect. You discover this in the lifestyle, in the activities, in the way people behave when you meet them. It is just the buildings that have changed but with regard to everything else, there is a commitment to culture, which we really enjoyed. PIETRO VALLE: In discussing cultural continuity, let's talk about the role of institutions in architecture. In Temple Bar, you not only inserted a new structure within an existing urban fabric but you actually defined public institutions that re-oriented the neighborhood towards collective use. Since we are presenting your school projects (and schools are another kind of institution), what do you think is the role of contemporary architecture in redefining public institutions? SHEILA O'DONNELL: We were lucky to be able to design a public building, or better a cultural building (I would not call it an institution) within the historic city. Working with the existing fabric helped us to think that buildings of the past and present all live within the same time frame and you have to imagine what meaning they would have nowadays. To think how an existing structure could embody a new function without being simply occupied by it was quite a complex undertaking: in the National Film Center it was cinema, a 20th century art, that had to be housed in a 18th century structure, an old Quaker meetinghouse. How does a building embody, or better represent, the activity that takes place in it? This was a critical point in the design and it took us a while to get to it but the search helped us to reflect on the relation between time and architecture. By chance, after Temple Bar, we have done a number of projects that transformed existing specific institutions, trying to find a new meaning for them. In the case of the Quaker meetinghouse, the existing meaning was benign. In another cases, it was less benign. PIETRO VALLE: Isn't there a tendency in your work to break monolithic institutions into miniature cities composed of different parts? I am thinking of the Ranelagh School as a series of houses or the Furniture College in Letterfrack as a composite landscape... JOHN TUOMEY: Absolutely. I think that's true. 'Institution' is an exciting but dangerous term because you are always tempted to orient it towards power but the truth is that we strongly believe in the idea of a democratic collective realm. It is interesting to be asked to make an institution because institutions do not always represent the best of society. However, it is possible to re-cast definitions in the way you make architecture so we tried to make the Ranelagh School as a little town. We are now working on the project to extend the school and it is interesting to us to come back and say "yes, it is not finished yet, it can grow" because towns do grow so why a school should not grow? It is ten years since we designed it and it was five years in use so we go back to a living organism that miniaturizes and idea of society or town. In contemporary Ireland, we have been placed in the role of putting back the belief in institutions or allowing the institutions to survive transformation without being evacuated. This does not mean that we think in 'institutional' terms: we always think in 'societal' terms. There is always a share of the public realm and this notion defines most of our architecture. PIETRO VALLE: Let's talk more specifically about three educational projects: Ranelagh, Letterfrack and Cork. They have different programs (public primary school, specialized technical facilities and public spaces for a college) in specific contexts: urban, countryside and campus... JOHN TUOMEY: The first one, Ranelagh, is a town, the second one is a reading of the landscape, and the third one is a pavilion in a park... SHEILA O'DONNELL: Letterfrack also deals with the transformation of an authoritarian institution with an amazingly strong memory while Cork takes place in a less charged landscape. JOHN TUOMEY: The art gallery, though, is very much a child of the other two projects. The whole effort to form the land on which the building stands is important. The building is not placed on pastoral land like a real pavilion: we build the land on which the structure rests and this base also forms an extension of the existing limestone escarpment that surrounds the campus. The plinth re-describes the structure of the place and once that task is done, the pavilion can rise. It is a structure that reads the site in the same way the as Furniture College does. Our first task in Letterfrack was to re-describe the form of the landscape and that came before functions, typology or budget. PIETRO VALLE: Materiality has a strong role in defining these projects. You are not afraid of composing parts of the buildings with different materials almost defining their city-like multiplicity in physical terms. In addition, your subsequent buildings are tectonically diverse form one another, having their materiality tied to different places... |

Art Gallery and Restaurant, University College Cork. East elevation.  North elevation.  Ground floor.  First floor.  Second floor. |

||

| JOHN

TUOMEY: The material approach, which is often developed by Sheila, sometimes

overrides other concerns in the design and brings a deeper resonance

to projects that otherwise, would be schematic or formal. SHEILA O'DONNELL: It also deals with the notion of the character of the place that can be reflected through its materials. It is important not to use local materials mimetically but to bring in another material through which the place can resonate. JOHN TUOMEY: You are not only looking for the visual effect, you are looking for the awareness that the material dialogues with the place... PIETRO VALLE: This approach goes beyond employing single tectonic categories like the expression of the frame or of the cladding. It also breaks the material homogeneity of a building. JOHN TUOMEY: On the day of the opening of the National Gallery of Photography in Temple Bar, there was a little party on the roof of the new structure. We were leaning on the parapet looking at the other side of Meeting House Square at our other building, the Photography Archives, and one of the founding members of the gallery said to me: "We are lucky, we got you as architects. You can understand the nature of our project. I am so glad we didn't get those terrible designers who did that thing across the road..." I thanked him but I did not explain that we were also the terrible designers who did that thing opposite... However, I was struck by the idea that for us our work is all part of a continuous process but one building does not look like the other. PIETRO VALLE: I think it is the best compliment you could ever get. JOHN TUOMEY: When we got the project in Letterfrack, it was a difficult task for us: first, the place is far away, second, the client did not have any money at all and, third, the brief kept changing, there was nothing fixed. We are still waiting to build some parts of the overall scheme. However, within those constraints that seemed to push for a quick solution, we still looked for intricacy and, in the first phase, we designed three entirely different structures, which express our interest in the idea of difference in a common project. SHEILA O'DONNELL: Things, though, are always changing and developing. We are not using this same approach in other projects: for example, in the schools we are designing for Utrecht in Holland and for Cherry Orchard in the suburbs of Dublin, we are looking for a kind of consistency throughout the building set against a suburban background, particularly in the latter case. PIETRO VALLE: This shows that diversity is not becoming a cliché in your work. You use it when it is needed. JOHN TUOMEY: We require this diversity from each other when we work together. Both of us articulate a position, in the sense that we do not operate without discussion. We expect that our work would be able to withstand discussion. This also means that we should be able to describe our work to non-architects in such a way that it means something to them without us changing our terms of reference. We were trained in James Stirling's office and he grew up in hard England where he could not express terms like 'aesthetics' to a client because the client would run away. So, he regarded architecture like a secret project discussed only by architects. This went on until he started working in Germany, at the same time we joined his office. We learned a lot from him because, at that precise moment, he was opening up, he was trying to relate what he was doing to what was going on in the world. With such an example, nowadays we would not be satisfied to have an idea that could not be described to someone who is not an architect. ELENA CARLINI: Architecture is becoming increasingly elitist and practitioners speak a completely specialized language. JOHN TUOMEY: "Would you like to live there?" "No, I wouldn't like to live there" We can cut a lot of stuff by just asking this question. Doing both the Ranelagh School and the Furniture College, an important task was to give the people who commissioned them concepts that they could claim as their own. You are talking to boards of local farmers or members of a cooperative and you are discussing quite complex ideas like landscape structure or deformation of typology or transformation of institution. In order to believe in the project, they have to think it is their own idea. SHEILA O'DONNELL: It is about ownership. We strongly believe that the buildings we design are owned by the people for whom they are made. You have to feel that you can appropriate the buildings. We have been quite lucky in these projects to have always had enlightened clients and, in the case of Letterfrack, we went through amazing group meetings, first with the board and then with the locals, the shareholders of this company, groups of almost 100 residents of this remote peninsula in the west of Ireland. JOHN TUOMEY: Regarding the workshop buildings, we said that they are leaning in the wind because in the west of Ireland no tree grows straight due to the strong Atlantic air fronts. So we said: "imagine that the workshop is a barn that has tilted and it has tilted because of two reasons, one is the wind and the other is the power of the central institutions towards which the buildings are leaning". That whole group of people got the idea and this allowed them to imagine that they could build a building that did not look like any existing structure in that area. In the Gallery in Cork we developed a similar narrative to describe the project from the clients' standpoint. We went to the College Board and said "Imagine a timber vessel raised among the trees, adapting to the presence of the trees around it and with views up and down the river". By re-phrasing it to ourselves and to them, the project became increasingly clear and evolved. SHEILA O'DONNELL: For the Ranelagh School we worked in a similar way. A lot of time passed between design and construction but, at a certain point, we had to come up with a pamphlet document entitled 'The case for a New School' In it, we also imagined the building, describing it as having a hard face towards the street and being more open in the back. JOHN TUOMEY: Our main reference for Ranelagh was Mackintosh's Glasgow School of Art whose simple diagram makes it the ultimate rational project. It has straight corridors, stairs at the end, a slightly asymmetrical entrance and a categorized spatial typology of studios, which involved no structural interruption. Mackintosh, without his flowing lines, could go to a party with Giorgio Grassi and our Ranelagh school starts with the dead straight line, the rooms in the front, the offices in the back and the playground behind. It is very enriching, though, to think that the skeletal structure doesn't supply you with the building solution, it only gives you a diagram around which the building evolves. After that, there is the idea of the brick, the idea of the timber and the idea of the school as a small town. The diagram has no complications but, by being typologically rooted, it can achieve enormous complexity, which gives you great freedom and can be communicated to others. PIETRO VALLE: Given your wide spectrum of references, what are the architectural practices you are most interested to in Europe? JOHN TUOMEY: Well, we are very fond of the kind of severity of British architecture in the 1950s. The New Brutalism is really the core. SHEILA O'DONNELL: When we were students we read all the stuff by the Smithsons and Banham. JOHN TUOMEY: It is still really exciting for us to meet Alan Colquhoun because we know he is coming from that period. Looking more at the present, we are very attached to the whole Porto School. We would refer to Portuguese architecture as exemplary. Part of us resides in the Scandinavian sensibility, not so much contemporary designers but the whole modern tradition of Aalto, Asplund and Lewerentz. We have no interest in what is happening in France. We are totally out of step with contemporary Dutch practice that, nevertheless, has become a world phenomenon. It is extraordinary the semi-psychotic condition of coming from a country that has no land form. That whole school of architecture is desperate for a hill and they make any kind of manipulation of the slab in order to mimic a topography they are lacking. But then that psychotic condition sweeps the world and everybody imitates it. SHEILA O'DONNELL: They managed to convince a lot of people that theirs are universal issues but in reality, they are not: they are just specific to their place. JOHN TUOMEY: Their problem is not our kind of problem. |

||||

|

Photographs and drawings: courtesy of Sheila O'Donnell and John Tuomey. Thanks to John McCourt for the revision of the English text. |

||||