|

|

| home > files |

| Peter

Cook interview Alessandro d'Onofrio |

| [in italiano] | ALESSANDRO

D'ONOFRIO: In your works lie strong contrasts, they appear to bring

their inborn tensions to the extreme; which motivations regulate such

mechanism and how is it controlled? |

[20jul2003] | ||

|

PETER

COOK: I think it is related to a preoccupation which I have about history

which is at the same time a very cynical and opportunist attitude to

history. I am not a contextualist in the sense that I want everything

to stay as it is. I am not a contextualist in the sense that. I want

everything to stay as it is. I am not very good in deserts, I very much

enjoy layered territories, where there have been different activities,

battles and famines, a lot of rains, and something stupid happening

and some funny politics, some good architecture, some insertions by

people wanting to do something and so on. So if you look at most of

Europe, you do not look at a land as God made it, we are looking at

a collage, a continuous collage of events and interventions. I, in many

projects –early ones and current ones– am interested in the conjunction

of the very artificial, the very manufactured and the natural and the

left behind. In the early projects such as " the lump" and "the sponge"

and "the landscape" projects I was always inserting pieces of, in a

way, High–Tech architecture into what appeared at first sight to be

nice and romantic countryside and have always been interested in the

idea of the extremely sophisticate finding themselves amongst the natural.

I think one has to take any of the European traditions of bringing some

architect out from the city with all his ideas that are contrivance

and mathematics and beauty and culture and exaggeration. ALESSANDRO D'ONOFRIO: In a designer's activity which role can teaching play?  Berlin Breitscheidplatz. PETER COOK: I think that the problem with many designer teachers is that they keep teaching when they're on the drawing board, whereas I think sometimes you have to switch off and just say "to hell with it anyway. I want to-do it like this". What you do as an alternative to those two things is probably work together with people you know and trust and are intrigued by; what happens on the drawing board is a kind of debate but in the end I think that I have the greatest enjoyment and delight in just saving "What's got to there" and you do it. And then you can give a long lecture about it afterwards. I love post rationalization. Every time I lecture about my work I am usually saving something that I thought about it when I was doing it, but what I thought comes out from what I was thinking while working. It is as if the idea doesn't stop when you have a line on the paper nor when you have the actual thing sitting there on the ground. ALESSANDRO D'ONOFRIO: Which elements or considerations (either rational or irrational) enhance your project process: any emotional suggestion or clearly determined data? |

||||

|

PETER

COOK: If I spend a good weekend, two weeks or there weeks designing,

I am much more critical, I am critical and optimist, I realize it, I

am bouncing, I am able to be more critical, with the students. I tell

them what is rubbish and what is interesting. I am not an academic.

I need to design to get my thought much clearer. I don' t get a buzz

from books, I read but at present spend more time writing. I am much

more interested in writing than reading, writing absorbs me completely.

I don't get a buzz from a significance between two philosophical ideas.

I get a tremendous buzz from noticing something on a wall and I begin

to invent stories as a writer. I am more journalist than academia. I

am fascinated by the phenomenon but I am bored by abstract. If I am,

forced to, I can play the game of course, but abstraction bores me.

Now in the architectural academia I am surrounded by more people that

play with abstract but have no vision, no eye. They have a whole system

supporting them: academics, the PH. D. to teach at the university, publishers

and all this mythological industry which in my opinion has nothing to

do wit architecture. But I know that in 20-30 years time people are

going to wake up and say "What were they doing at the end of the 20th

century "It had nothing to do with architecture!". As we have laughed

at the debate between Romantics and Classicists at the end of the XIX

century, or thinking about our idea of Empire, we think "How could they

have so stupid?" at certain moments in history. ALESSANDRO D'ONOFRIO: In your last project, -I am a referring particularly to the Project Pfaffembourg- it seems to be a concept of the city based on the relationship among the single elements. This operation arises through the idea of "net": a sort of subtle and irregular mail which tends to get loose until it covers the whole urban area .Do you think that this concept can be ideally related to the experience of Instant City? Moreover, do you still find any significance in the "city" since it has developed in such outstanding way so that it has lost the definition of its borders? The loss of such identity reminds us cities such a Los Angeles, Tokyo, Mexico City: Do you think architects must try to manage the development of a city or on the contrary shall they make single, limited interventions? |

Moscowhawco House, Moscow. |

|||

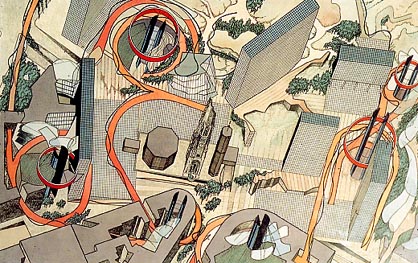

Pfaffenburg Museum, Bad Deutsches Altemburg; Belvedere. |

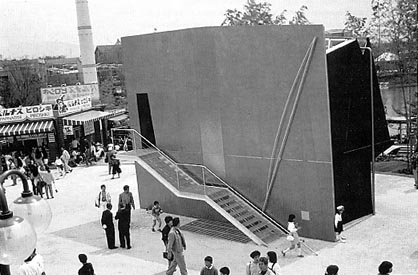

PETER

COOK: I think the marvellous thing about cities is their ability to

absorb. If you think about them sociologically, we live in cities to

meet more interesting people. In the country district you have to become

part of a narrower a more ordered society. In a city there is a collage

of all different sort of people. I think really good cities are those

not concerned with consistency but are absorptive of all sort of different

things, buildings, people, mechanisms and atmospheres... It cam be argued

that in order to build up a strength you have to have a coherent and

powerful base but I am not so sure and it depends on personal taste.

I like an agglomerate city, a funny city, a city where you are not interested

whether it is proper or not. I like the mixture of a manufacturing city

and a governmental city; mixture of communication cities and intellectual

cites. I prefer Antwerp to Brussels, Milan to Rome, Glasgow to Edinburgh,

Tel–Aviv to Jerusalem. London nearly gets it right because it lochs

having as many manufactures as it used to, so now it is beginning to

be too little of a making town... but this is my own romanticism. In

the end the most interesting are those which are inventing, which tend

to accompany manufacture and people striving to do something. The problem

with government cities it they tend to be bourgeois, conservative, people

who are in love with the past and the status quo. Thus, generally speaking

I find those cities less amusing. L.A. and Tokyo I love. L.A. is one of my favourite cities, it intrigues me because it is absorptive of an extraordinary variety of people. It has that dream of the impossible, the escapism which is essential for 20th century survival. It is not an accident that it is the city of the movies, computer art, virtual reality telecommunications and space technology, all have to do with escape which I feel is the life of late 20th century. More and more, survival is a mixture of reality and theatre. I think great cities have had to do with theatre; for example Rome with the Pope around the corner, the mythology of the Pope, what's the difference between the Pope and Hollywood? Nothing, but we need this because if you go to a bland city there is no room or imagination. But I am very hedonistic in my use of cities. I suspect I am a dying breed in my love for L.A., probably I am in love with an idea of L.A., which no longer exists. ALESSANDRO D'ONOFRIO: Your image of the future, or in certain was of the city of the future as it could be Los Angeles, is reassuring; are you optimist?  Osaka Pavilion. PETER COOK: Yes, of course! We have no alternative to optimists. Culturally, if there had not been any optimist we would not have discovered America, electricity, nor built an airplane, nor discovered medicine. People would have said "There is an ocean there and who knows what is over there?" Optimists make boats... My view is we would not be alive now if it weren't for optimists. Otherwise we would be living in a different world. I think optimism is inherently a part of survival and civilization, without it we would not be here. Pessimism is suicide. ALESSANDRO D'ONOFRIO: You seem to have a double vision of progress: on one hand it is intended as a possibility of ransom of e man condition, on the other hand it is intended ironically. |

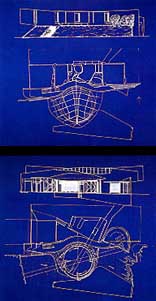

Pfaffenburg Museum, Bad Deutsches Altemburg; Open Air Theater.  Pfaffenburg Museum, Bad Deutsches Altemburg; Museum Pavilion. |

||

| PETER

COOK: Progress is related to optimism. It was considered progress to

go over a sea and find something at the other end which was called America.

And this enabled Europe to survive as a civilization. I hate to think

what would have happened to Europe if America had not been used as a

sump to ditch a whole lot of people over there. It would have ended

up as something floating out there like China which has a glorious past

but miserable presence. I am very cynical about these issues. But of

course one has to believe in the future. ALESSANDRO D'ONOFRIO: The myth of modernity is undergoing a strongly dichotomy phase. In Europe it is expressed through the High–Tech, while in the United States through the Deconstructivist, i.e. two opposite vision of reality, the first one aiming at objectiveness, the second one to the most extreme subjective ness. PETER COOK: I think High–Tech is intriguing because in a sense it is alien to the general drift. I am not sure if High–Tech is the preserve of a mysterious group of species of animal that is in a strange place at a strange time. Or perhaps it is a bridging operation until the real High–Tech starts. It is intriguing to me because the two most important countries that are the core right now are England that started it and France that is developing it. Americans really do not understand and Japanese sort of do, they use it, they don' t develop it. But really the core of the High–Tech world is between London and Paris. This is fascinating because two of the oldest countries that should have given over already but both countries have a strong inventive tradition and good engineers. Both countries are full of people who would go away to find a better way of making something where I think a lot of countries fear that. I think the Americans are not actually progressive. I think they have a power but are not natural innovators. It is interesting because High–Tech started in England about 25 years ago and now the French architects seem to be running with it almost more than young English architects. Somewhere between Norman Foster and Jean Nouvel is an extraordinary powerful thing. It is an extraordinary powerful thing. It is funny that it is in those two countries almost touching each other. ALESSANDRO D'ONOFRIO: Which is the relationship between High–Tech and your work? |

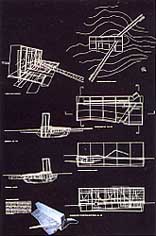

Plug-in-city. |

|||

Paris Housing. |

PETER

COOK: It has to do with a tradition of invention. A tradition of eccentric

engineers because it is a engineering tradition which architecture has

been lucky to pick up on. I think the most important in both countries

are mostly engineers. Certainly in our own town we have been very lucky

because since the 30's there has been a stream of engineers, some of

who were refugees from Nazism and a whole collection of strange people.

Now we have brilliant. Then there is also a linking with people working

with Germany, for example Frei Otto around the Sixties. Now it is like

an export because these engineers are doing things around the world,

i.e. China, Japan. Thus when you look at Kansai airport the actually

cutting edge stuff comes from Genoa and London. I think if that if this

has happened in recent years maybe the mainstream of architecture is

always going to be crap but what is important to a culture is the standing

of the special architecture and how much that can seed into the world

at large. Thus, is a Way it is a challenge to contextualism. An idea may be generated from one place and transferred to another. I have a small son and I learn a lot from his toys. For example looking at the box you can see that the design was done in Cincinnati or Birmingham, the box may have been manufactured in U.S. or Hong Kong, the marketing in L.A. or Paris, the toy fabricated out of China but distributed out of Důsseldorf and the kid could be anywhere in the world. The question is what is that object culturally, where is the idea coming from? We cannot say exactly where it comes from. It is the same way as we get cars things come from all different parts of the world. Thus it is only going to be in time that we get buildings the same way i.e. from all over the world. Centre Pompidou was like that and it is already 20 years old. It was designed by Italians and English, (French were not good enough at that time); the assistants were Austrians, Japanese, Italian and English. It is a fascinating territory because it sits in France as a French cultural centre. I love it. ALESSANDRO D'ONOFRIO: ALESSANDRO D'ONOFRIO: Do you think your work is somehow related to the American Deconstructivists? |

|||

|

|

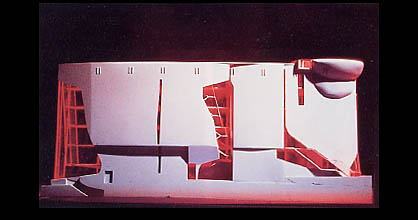

Hamburg Office, Hamburg. Model. PETER COOK: The connection, if there is any, would be with the key group of Deconstructivists architects, who were in the Museum of Modern Art exhibition, many I am friend with and I have watched them develop for example Zaha Hadid, Daniel Libeskind and Frank Gehry. The Deconstructive application of certain philosophical ideas to what they do, I find it personally boring. I have not read much of Derrida, I read three pages and was irritated by his self-conscious cleverness. I think I know the above-mentioned architect pretty well and I am partied to many private conversations about what they do and how they do it. I think the reality of Deconstruction is a continuation of expressionism. I think the espousal of certain philosophical ideas to prop it up is an amusement to academic and to people that have no eye but I think to anybody that has an eye the linkages are quite different. There was bound to be an explosion of Rationalism and Constructivism. I think it is intriguing to me because now, the particularly people involved are trying to move on. They are trying to identify themselves, is a funny way, as pragmatic architects because they are not pragmatic architects because they are not pragmatic architects. I think the problem is the question of cycles of ideas and cycles of influence in terms of what gets built. I think there is always a problem with architecture at what you do, how you explain it and how it relates to the general speed of movement. For example in countries that do not have a very developed architectural conversation or an underdeveloped country, you get a jumping process but the miss out on 50 years of conversation, all the background is lost. Or you have overfilled countries when just as things are going well it is moved on to movement. This is also to do with modern life i.e. publishing, TV etc., where you get an almost discuss only situation. For example Danny Libeskind will get no an airplane almost anywhere; one week Ireland, the next Africa, but the conversations which have developed around him are there. I think the problem is the question of cycles of ideas and cycles of influence in terms of what gets built. I think there is always a problem with architecture at what you do, how you explain it and how it relates to the general speed of movement. For example in countries that do not have a very developed architectural conversation or an underdeveloped country, you get a jumping process but the miss out on 50 years of conversation, all the background is lost. Or you have overfilled countries when just as things are going well it is moved on to movement. This is also to do with modern life i.e. publishing, TV etc., where you get an almost discuss only situation. For example Danny Libeskind will get no an airplane almost anywhere; one week Ireland, the next Africa, but the conversations which have developed around him are there. ALESSANDRO D'ONOFRIO: Unlike other architects you have always cooperated with friends, group of artists, teams; do you consider cooperation as a necessary condition to enhance your creativeness? PETER COOK: I think I am very English because I do not expose a lot of nerve endings but I am very emotional. I enjoy the mixture of that. I enjoy the system. I work in which is a very quite system so I can be an excitable person in a quite system. I have found when. I have been in more excitable systems, i.e. Mediterranean ones. I con not get through because so much energy is used for surviving. I think I am also affected by people. I think Christine Hawley and I have worked together so much because we share a sense of humour. We appear very different from what we are in reality. For example if we are working on buildings we invent incredible comedies about them. We put characters with names etc. I think there is irony and play. Ironic stories appear to us playful things are serious and inventions are playful. We like it like this, we suddenly find a place to put the cat basket under something else and the result is something struck out from the wall and cast an intriguing shadow which just happen to be a certain geometrical point that links to something else. What I mean it is not the philosophical idea but it was the cat in the cat basket. It was pragmatic but based on something extremely random. I think in history this is what happened. There are two people who want to cross a river and they have a problem of a fat friend and they have two tree; so they make a bridge. Ten years later another fellow will came around and say "What a good idea!", but all came from the two people whit the fat friend and the two trees who had to pass the river. Certain situations occurred and from then on they continue this way. I believe that architecture is "bull shit", meaning that it is like the inhabitant landscape which is also "bull shit", we think the landscape is land, bat actually it is influenced by a several events: a very cold winter or the fact that the second son of the farmer was stupid, there was always something that was happening unplanned. |

|||

Dampstead Housing. |

I

think architecture is like that, that somebody built a door because

they had a special requirement but they do not write down for future

generation what that was. Then somebody else come along and changes

certain things, which become fragment that built up as series of symbolism

built around the fragments. Let's take the Corinthian column, nobody

knows exactly it was like that... I think if any of the High-Tech buildings

survive to the end of the 21st century, certainly someone looking at

a particular piece of metal fashioned that way will say it was part

of a religious cult that led it to be like that. This is wonderful;

it is the same principle as the language evolves. Architecture is a

mixture of function, mythology and arrogance. Architecture is arrogant

which is fascinating. Otherwise it is just re-building. One a day some

arrogant people came along who is arrogant enough to decide to built

a roof on a wall. I teach architecture and I am encouraging my student

to get something out of their "bull-shit". I do not think I am strange,

because the same takes place in literature, in journalism, in shoe manufacturing,

otherwise we would have only one standard of shoe! Culture is a "bull-shit", is wonderful! I say so because I think I am being a little provocative, I hope I am, because I know the majority of architects, students, academics, critics, people who write about architecture, people who build buildings, they want three to be order, they want to be told that what they do is right; they want to have a formula, an access key, a neat plan. If they did not if they were all pragmatics, I probably would be arguing the opposite, but, as it is so... And in Rome there are more classical rubbish then anywhere else, thus I am forced to shout my corner. |

|||