|

|

| home > files |

| Towards

a history of infrastructures Antoine Picon |

||||

| redazionale |

||||

| [in italiano] | For

a long time motorways did not have any history, at least not in the

awareness of their users, who saw in them a symbol of modernity very

different from that of the road and its sometimes millenary compromises

with the land traversed. Indifferent to local routes, at times capable

of spanning whole valleys as only railways had previously been able

to do, motorway infrastructures seemed directed more to the future than

to the past, towards a national and international geopolitics of circulation

rather than towards the slowness and delays of ordinary main-road traffic. Then the motorways aged, like their almost contemporaries, the airports. New generations of motorists appeared who had never known anything but the motorway for their holiday journeys. An excess of familiarity often breeds its opposite: astonishment in the face of the order of things. It was no chance that the naturalisation of the motorway proceeded at the same rate as the first systematic research into its origins and development, and similarly into its role in the recent history of countries such as Italy, Germany, Spain or France. |

[23jan2006] | ||

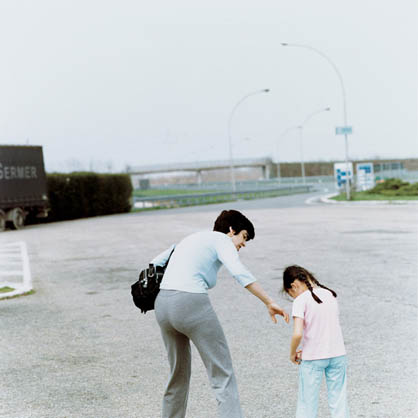

Giorgio Barrera at Rio Cocchi est.  Francesco Gnot at Priero est. |

Guido Guidi at Mondovì ovest. A new object of study, the motorway thus completed the range of technical systems studied by the history of infrastructures that has flourished remarkably in recent decades. When new and often recent objects, such as motorways, made their appearance alongside older structures and networks, like roads, canals or railways, the issues changed. To put it briefly former studies on the history of infrastructures concentrated on economic and technical history, and on the analysis of the urban and architectural picture. The new history of infrastructures, drawing to a conclusion today, has, instead, been more ambitious, since it aims to integrate fully with political, social and cultural history, rather than pass for a specific field with well-defined boundaries. |

Ciro Frank Schiappa at Rio Coloré ovest. |

||

Michele

Bonino and Massimo Moraglio's work falls perfectly within these dynamics,

being at the same time one of the first monographs on the history of

an Italian motorway, the Torino-Savona, and a reflection on the nature

of this type of infrastructure in contemporary Italy. [...] The old and the new roadway in the loop area, Altare (SV). The definition of motorways as the "non-places" of modernity, to use an expression created by Marc Augé, is even more persistent than the notion of an infrastructure with no history. Like airports, motorways often find themselves inserted into the category of structures lacking specific characteristics, which contribute to defining a generic urban and territorial condition, leading to the repetition of the same landscapes from one end of the earth to the other. |

||||

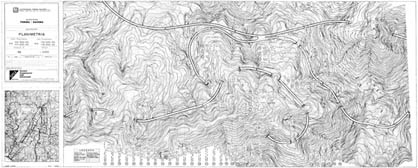

With the complex vicissitudes that characterised its construction

in various succeeding phases, the Torino-Savona motorway glaringly refutes

this type of theorising. Its special features, some of which border

on the absurd, such as the loop at Altare, the succession of structures

marking the entrance to Millesimo, or the astonishing Vispa service

area, with its kitsch decoration and shelves lined with local produce,

may stand as examples. Certainly, the conception of motorway structures

always involves a generic element, although closer study also reveals

the existence of national, sometimes regional, specific aspects. But

not for this are motorways "non-places" destined to banality.

Regarding infrastructures, complex links in fact combine the generic

and the specific. The infrastructure reveals the place in the very moment

in which it tries to negate it in the name of supposedly universal technical

and economic logics. Viaduct over the Pesio river, late 60s. ATS archive. |

||||

| On

this point, it is useful to recall that the birth of tourism, based

on the perception of the unique quality of places, was intimately bound

up with the development of the railways and then the panoramic roads

in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. In many cases, the motorway

took their place, revealing the physiognomy of the regions passed while

indefatigably rushing towards other regions, other horizons. The Torino-Savona

is undoubtedly a part of those connections that contribute to enhancing

their surrounding environments. [...] The book contains many illustrations. Some date to the construction and earliest use of the first stretch of the Torino-Savona motorway; others have been shot recently. All have a landscape dimension in common, which today merits consideration. |

||||

Ceva junction, Summer 1965. La Stampa archive. |

The

motorway infrastructure does not limit itself to revealing the landscape

by opposing, for example, the direct line of its crossing structures

with the undulations of the ground. Certainly, the infrastructure lies

in the heart of the countryside like a giant picturesque garden construction,

which contrasts with its surrounding natural frame the moment it starts

to resonate with it. But the infrastructure itself creates the landscape,

by means of the tension it introduces between a here and an elsewhere,

between the visible and the invisible, between the present and the future.

The motorway is simultaneously a reality and a promise; the reality

of roads and structures and the promise of distant regions, whose existence

can be sensed immediately beyond the horizon. Between the here and the

elsewhere almost infinite possibilities of narration arise. A very particular

picture of the motorway lends itself especially well to exercises of

the imagination, as directors like Wim Wenders have understood. This

narrative potential makes everything that remains landscape, and renders

the motorway infrastructure highly photogenic. Other perhaps more disturbing but equally seductive stories and inventions have followed upon the founding tales of modern Italy, that of rapid industrialisation or of the motor car and mass tourism, and upon the inventions that were grafted onto these. The contemporary landscape of infrastructures is disconcerting in many ways. Based on violent contrasts, peopled with objects of an uncertain nature, half-way between technical system and traditional construction, such as the motorway toll booth, it no longer shares anything with a Romantic painter's Arcadia. It attracts and disturbs at the same time. It talks to us about who we have become, about who we are. Between reality and promise, the motorway is not a thing, but a landscape - a human landscape. Antoine Picon |

|||

| >

ALLESTIMENTI: CINQUANT'ANNI DELL'AUTOSTRADA TORINO-SAVONA |

||||

|

|

ARCH'IT

books suggests: Michele Bonino, Massimo Moraglio ( a cura di) "Inventing movement. History and Images of the A6 Motorway" Umberto Allemandi & C., 2006, pp192 |

|||||

| Per

qualsiasi comunicazione laboratorio

|