|

|

| home > lanterna magica |

| Reverends |

||||

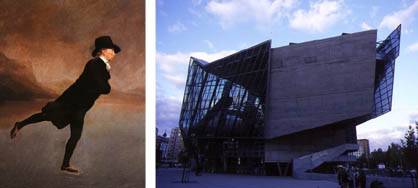

Sir Henry Raeburn, Reverend Walker, 1790 |

||||

| [in italiano] | Reverend

Walker, immortalized by Sir Henry Raeburn, makes us reflect and it offers

to us as a useful lesson. That legendary portrait depicts the most elegant

and ethereal idea of fun (ice-skating, to be exact), played and enjoyed,

anyway, with the very large trust of the person who knows to have to

answer to men and above all to God, of a surplus of movement. So, Reverend Walker is not sliding, for he is stuck in the sliding. When Sir Henry Raeburn painted that portrait, he didn't represent only a person who is sliding, but someone who shows himself as a person who has been sliding from the beginning and for ever. This picture shows us a representation raised to the square: when Reverend Walker had his portrait painted, he was already the subject of a representation, and he shifted skating on ice to the music of an English horn; so, he seemed a sort of self-portrait, a marble herm, provided with simple walking appendixes to link their owner to the ground level. Reverend Walker (whose name already enlightens him as somebody who is bound to move on), slides just for the edification of his audience: he shows to the supporters how to slide without any actual sliding, he represents the most abstract idea, or the quintessence of sliding. He represents the most unbridled and youthful fun, but no one, except for those who are biased and malicious, could say that Reverend Walker is really enjoying himself: on the contrary, he's working hard for the edification of mankind and above all for the benefit of his faithful parishioners. If he was reading a sermon aloud, he couldn't appear more measured; and even if, reading a sermon, skating on ice or walking along the antipodes, he fell down, his fall would be glorious: he would go straight down into the icy water without turning any hair , immobilized waving at the flag. Sir Raeburn could have painted the Tower of Pisa, the Egyptian Pyramids or the Ara Pacis during his trip on rollerblades towards the wonderful Cathay, but couldn't have achieved such a monumental result. Probably, we imagine that we can smile of all this, convinced that two hundred years haven't passed vainly. Even if all this is true and many things have actually gone on changing for the last two centuries, anyway, I believe that we cannot easily laugh either at the skating reverend Walker, or at the painter of his portrait. If we consider that in 1790 the movement had to be represented with a certain parsimony, we can realize that reverend Walker carries out the same exercise we can see acted by the much more celebrated and fashionable second immovable, by his side. Both the immovables seem to be plastered in their moving, and both "posed" from their beginning. We shouldn't let us lead astray by the breezier look of the present construction which I chose not so much for its charm, but above all for its typicalness, as representative of a lot of other fashionable and floating immovables: they are really alike. First of all, in spite of appearances, neither the iper-fashionable immovable lives it up. It is working hard for us and it wants our edification; it is portrayed in pose for the benefit of the parishioners. Moreover, it represents a comedy. It mimes a catastrophe, performs a sort of melodrama, based on the suggestion of collapsing structures. Anyway, only biased or malicious people could affirm that it is actually collapsing. On the contrary, if we want to approach that structure we must suppose that it enjoys good health, otherwise, neither the most fanatical supporter of orgiastic iper-fashionable pomps could induce us to do it. So, even the second immovable plays a script and talks from a pulpit. Of course we cannot think that a profane and iper-fashionable immovable, blocked between the stroboscopic lights of a disco, in the very moment the disk-jokey shakes phosphorescent lamps which send out flashing laser rays towards the girl dancing on the cube, looks prim as a ripe clergyman when Jane Austen was still a teenager. It would be to demand too much. So, that iper-fashionable immovable updated its disguise, but the substance seems the same. Both cases give us the representation of an immovable that wants to depict itself already amused, amusing, and always on the go, right from the start. So, what has actually changed for the last two hundred years? I believe that something has changed. Of course, I don't want to let me ensnare by the fibrillations of history (revolutions, world wars, exterminations, atom bombs, television, computers, and so on), anyway, I'd like to underline that at that time the representation had to be acted in a very close place but not coinciding with reality, whereas today it does not recognize this precinct. Nowadays, even Reverend Walker would admit that such a heroic pose would be justified no longer, for an equestrian pose is utterly superfluous, by now: it completely identifies itself with reality. As the real studio is the world nowadays, we need suitable sets. Old papier-mâché sets would be pathetic, because they don't answer to the pressing expectations expressed by this reality show, any more. If it's reality (whatever we intend using this ancient word) that must be "broadcasted live", if it's reality, the unique show of our time (always in real time) true scene designer has to work on it. |

[20jul2004] | ||

| Reality,

and above all architecture (I'm talking about architecture, though I

know that the word is inadequate, by now), will have to take a scenographic

role, without any mediation. The main difference between an architect and a stage designer is not based on a different technological status of the two disciplines, or more or less on the durableness of their products: in my opinion they are so different because one "builds up", the other "edifies" an audience and while the architect doesn't care about "representation" or "self-representation", the other is always engaged in representing something for the benefit of somebody. This is one of the reasons for which although the photography of architecture never had similar technical resources, it never achieved such a level of vulgarity. It's photographers' responsibility only in part (That good fellow of Sir Raeburn is responsible for that portrait of Reverend Walker, only in part): the poor photographer is already facing a posing subject, an immovable that mimes a movement, an unshakable that plays catastrophes, a plastered subject that kneels down, a hippopotamus that wears a tutu. Anyway, the honourable Reverend should be surprised at the plenty and power of his unexpected followers. Yet, I guess, his "followers" might be surprised and bored, to be defined unintentional epigones. As they are the cream of mankind. Those great Reverends of iper-topical/iper-fashionable. So Reverend Walker will be obliged to adapt to the role of precursor not recognised in such a way. Nowadays the most complete ideologization is realized through the persuasion (mostly yelled) to think on one's own way and to be numbered among the free spirits and the titanic creators. As a matter of fact, there are just "creative people": except me and a few dinosaurs, already completely sentenced to the grinders of evolution, it's impossible to find a middlebrow person even paying a very high price.. Have a good time. Ugo Rosa u.rosa@awn.it |

||||

|

Traduzione

di Daniela Di Vincenzo.

|

||||