| [in

italiano] |

|

The

year 1978 was one of crisis both for architecture and for Peter Eisenman.

The postmodern movement in architecture, based on a cultural approach

that would soon become laden with historicism, was increasingly taking

shape on the international scene. In Italy, where little architecture

was being done, or had been done, a few post offices with arches and

columns, and a Hollywood-style scenario with half-busts in plaster

in an earthquake stricken town in the Valle del Belice, were built.

But in America, where more architecture was being constructed, there

emerged a generation of office buildings, university campuses, and

even skyscrapers that are more reminiscent of neo-Gothic film sets

than of a serious study of the environment and the city.

In

the cultural environment generated by postmodernism there were not

only formal veneers of kitsch but also serious questions, still unresolved

53 years after the Exposition des Arts Décoratifs in Paris

in 1925. There were two themes in particular: first, the need to go

beyond the modernist taboo of "pure" formal research, and

second, the awareness that architecture belongs to a specific place.

The concept of context emerged as the fundamental theme of these years:

on the one hand, because the Western city's period of expansion had

historically ended, work was directed toward the spaces between existing

buildings, and on the other, the idea of context developed an awareness

in planning of relationships to an existing environment.

In 1978 Eisenman was in crisis because postmodernism was pushing in

a direction stylistically opposed to the research he had carried out

until that time. In addition, an absolutely key work in his development

in the 1970s, House X, was not built, and instead became the subject

of extensive graphic representation. This latter development was also

due in part to an event in 1978. That year, Eisenman was asked to

participate in "Ten Projects for Venice," a planning project

organized by the Architecture Institute at the University of Venice.

The area of study was the Cannaregio, at that time run down and unused

after a formerly distinguished industrial life. Eisenman proposed

an ingenious architectural process that contained and anticipated

the main enzymes of the town plan as it was to develop over the two

subsequent decades. He used the theme of place and context as the

main thrust of his architectural reasoning but in a way that completely

abandoned the postmodern clichés of adaptation and mimesis

and moved in a more conceptual direction. Eisenman organized the Cannaregio

with a series of grids and positions that he took from a close reading

of the city and its stratifications, as well as from Le Corbusier's

Venice Hospital project. On the basis of these force lines he formulated

a grid that literally restitched the existing with the new project

and organized the spaces and buildings as if they were regulated by

a single force. Buildings (in this case, various scalings of House

XI) were placed at strategic points inside this new campo,

and a reasoning that contained the architectural idea of layering

was triggered (that is, autonomous subsystems, each equipped with

its own structure, function, and position, when laid one over the

other defined the overall project).

Eisenman's Cannaregio employed an ingenious and revolutionary technique

that used the theme of context as a catalyst of the crisis. Context

here is no longer the inspiration for historicist settings in a postmodern

style but is the source of intensive study. As was the case with old

medieval maps, which were written on by partially erasing the older

texts, Eisenman sought lost meanings and geometries that could be

used to structure the new. The context was thus seen as a palimpsest,

but it also carried a series of narrative, metaphorical messages.

Architecture also tells a story and has a presence made up of multiple

layers of meaning: past and future, geological and urban, abstract

but also subtly narrative. Cannaregio was proposed, in short, as "boring

into the future."

The strength of this approach was seen shortly after in Eisenman's

residential building for the IBA in Berlin and gradually in his subsequent

projects, as well as in the work of other architects who sensed its

strength. For example, Bernard Tschumi's plan for La Villette in Paris

combines his own research into the discontinuous movements and syncopated

editing of cinema with Eisenman's reasoning on grids and layers.

Castelvecchio today is inconceivable without Cannaregio yesterday.

In the operation Eisenman has proposed for Verona in 2004, some 26

years after the Venice project, many notable points develop this antique

path of research. Primarily, the architect chose not to celebrate

himself through an exhibition of his work but rather proposed something

both more modest and more ambitious. He is not exhibiting himself,

but his ideas. He has in fact many times said, "I want to be

remembered for my ideas." Spaces, organizations, and fragments

of projects that are indicative of his thinking (from Cannaregio to

Santiago de Compostela) emerge in sections of the plan. In Verona,

too, grids and close readings of the historic stratifications create

the structure of the new plan, but a difficult vibration, a "pure"

intuition, almost imperceptibly takes shape between the elements of

that way of working.

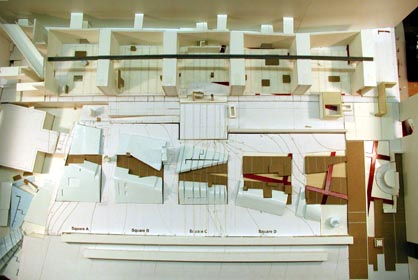

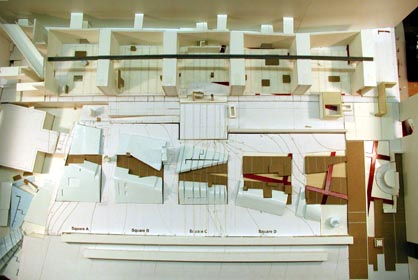

On the one hand, the Castelvecchio installation shows one of Eisenman's

most powerful convictions. For him, architecture is primarily a "critical

practice." Indeed, the conceptual origin of the plan lies in

an awareness of the "slightness" of the wall (decked out

in false antique in the 1920s) that separates the sequence of Scarpa's

big exhibition rooms on the ground floor from the garden. This wall

was seen by Eisenman as if it were an immaterial diaphragm, which

allows him to bring the internal rooms into contact with the same

number of external piazze-rooms he set in the garden. In

this way the five big exhibition rooms and the same number of external

piazze establish a dialogue between positive and negative.

Furthermore, a second set of piazze are oriented on the axis

of the tower and Scarpa's famous pivoted bridge, so that the two systems

intersect. A grid "found" in this suite of piazze

then appears in fragments, or spirit-sculptures, that emerge in the

thin gap between the floors and walls in Scarpa's exhibition rooms.

In this dialogue between Eisenman and Scarpa, a well-rooted "critical

architecture" is overlaid by the thin, light, but very important

network of a "poetic architecture." Eisenman chose an apparently

secondary and trivial element of Scarpa's plan: the striped lines

on the floor drawn by the Venetian architect across the visitor's

route, give a dynamic, almost syncopated rhythm to the succession

of museum events. Eisenman "felt" the essence of these white

lines on the floor: they are the idea, implicit in Scarpa, that the

museum does not finish there, enclosed in those walls, but that it

extends outside its shell, into the city, into the atmosphere, into

history. Eisenman's intelligently critical and, above all, poetically

inspired operation was to understand the profound significance of

these marks and to use them to organize the structure of his plan

in the courtyard. He uses those lines move on the plan and in the

section in order to articulate the forms of the ground, the hillocks

and the canyon that mark the thoroughfare, and at the same time to

speak to us of Scarpa, of himself and of the great possibility of

architecture in the world.

|

|

[11dec2004] |