Architectural Design, vol 75, 1, Jan/Feb 2005, pp. 23-29. Special

Issue 4dspace: Interactive Architecture, editor Lucy Bullivant.

|

|

Interactivity is now the catalyzing element of architectural research

and development activity because it is within this that the contemporary

communication system, based on the possibility of creating metaphors

and so of firstly navigating and then building hypertextual systems,

resides.

Secondly,

interactivity places at its centre the subject (variability, reconfigurability,

personalisation) instead of the absolute nature of the object (serialization,

standardization, duplication). Thirdly, interactivity incorporates

the fundamental feature of computer systems, namely the possibility

of creating interconnected, changeable models of information that

can be constantly reconfigured. And lastly, interactivity plays, in

structural terms, with time, and indicates an idea of continuous ‘spatial

reconfiguration' that changes the borders of both time and space that

until now have been consolidated.

HYPERTEXTS

AND THE CREATION OF METAPHORS: INTERACTIVITY WITHIN THE WORLD OF COMMUNICATIONS.

Many of us will still remember the ways in which architecture used

to be taught us. For a long time, the key word was objectivity. We

had always to demonstrate analytically the relationship between a

cause and a specific solution; good architecture sprang from this

association. However, this way of thinking has now gone out of fashion,

together with the great industrial model. Today, narration holds pride

of place. Consequently, what comes first is the story to be told,

and it is only after and within this narrative that the project develops.

There are examples of this in front of us all.

Peter Cook and Colin Fournier, Kunsthouse Graz, 2003. The

interactive facade is by Realities United.

We

must also add a second factor to this narrative component, and it

is here that interactivity comes into play. More and more, contemporary

communication is also metaphorical. Metaphor replaces a unidirectional

cause–effect reasoning with pluridimensionality and the discontinuity

of rhetorical figures. Instead of in a linear manner, advances are

made by hops and jumps.

dECOi, aegis hypo-surface, Birmingham, 2002. Photo: Mark

Burry.

But

is not hypertext the communicative setting of these jumps? With HTML(hypertext

mark-up language), its links and the Internet, is hypertext not an

inalienable part of our way of thinking today? The most fitting definition

of hypertextual systems is that of being themselves settings in which

metaphors are created. The challenge in this sector lies not only

in creating predefined metaphors (for example, an artist's production

exhibited in his virtual studio), but also that of being able to have

‘mobile metaphors' that can be reconfigured each time by the

user. An ever-growing number of systems are able to create actual

metaphors that can be personalized (consider, for example, the creation

of scenarios that can be played or visited through the use of artificial

intelligence techniques, or searches in databases that can be personalized,

or virtual simulations). By this we mean that interactivity thrusts

the sphere of contemporary communication towards a more complex level:

metaphors and images that are already defined begin to be replaced

with the idea that we can ourselves create our own metaphors. This

is the great challenge of the world of hypertextual communication.

It is an open battle, one that is also political and social, and that

implicates the development of an increasingly mature critical sense.

When I teach, from the outset I ask all my students to create and

publish their own web pages: this is no coincidence.

INTERACTIVITY AND THE COMPUTER WORLD. Information technology is the

underlying ‘mental landscape' of today's architecture. By mental

landscape I mean that architectural research (since the outset) prefigures

the ideal context in which it is located. Architecture prefigures

this mental landscape by supporting some elements already present

in reality, developing other elements and, above all, incorporating

scientific or symbolic models that have succeeded each other over

time. That is, architecture transforms these models into specific

spatial interpretations.

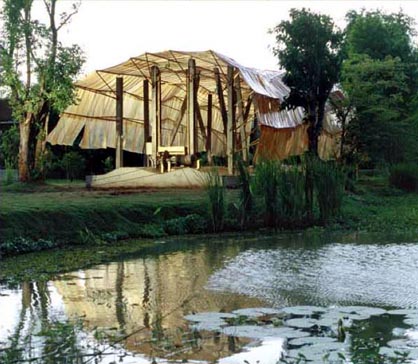

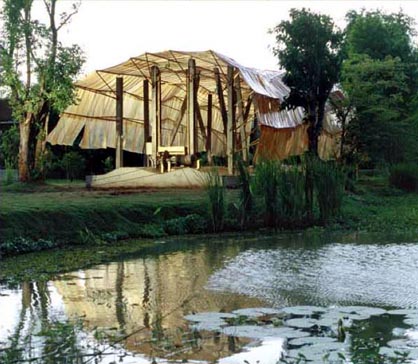

Philippe Parreno, François Roche, Hybrid Muscle, Work

and Exhibit space self generator of energy, Chang Mai, Thailand, 2003.

INTERACTIVITY

AND TIME. Now we come to the last set of considerations, which is

in some sense the most complex. Interactivity is associated with time,

which as Einstein himself wrote, is the only way to say something

sensible about space. Let us recall some fundamental concepts. In

the first place, space is not an objective reality (as we often believe),

but is perceived culturally, historically and scientifically in very

different ways. If we use time as a system for understanding space,

we discover something that is highly effective. The jump rule prevails

from one reference system to the other; it is the same jump that underlies

hypertextual systems. (If I live in and know only a two-dimensional

system – imagine a curved sheet of paper – in order to

go from one point to another, I follow a route equal to T. Even if

I curve the surface greatly, T still remains the same length. But

if I look at this curved sheet from a three-dimensional world, I immediately

note that A and B can be linked not only by segment T, but also by

a far shorter spatial vector, ‘t', which travels, or rather

jumps, through three-dimensional space).

Interactivity

in buildings can mean not only varying configurations and spaces according

to changes in wishes or external input (as we have just seen), but

also creating different systems of spatio-temporal reference.

|

|

|

|

|

|

If

an interactive system modifying architecture is linked to Internet-based

navigational systems, the effect of the jump can pervade the whole

of architecture: a jump from one spatial configuration to another,

a jump between different information systems and, finally, a jump

between different temporal states. Associated with window interface

systems, real-time navigation systems, remote depiction systems with

naturally interactive, hologram-based systems (a brief step forward

that will shortly be made), the great world of Internet can form an

incredible ‘thickener' and multiplier of spaces and times. We

can have windows open at the same time on worlds far distant from

each other, and literally jump from one to the other: live in them,

try out accelerating or moving spaces, show and be shown, and all

this in real time and in a continuous jump from one world to the other.

The Internet is a necessary instrument for architecture in this stage

of research, not only because of its pragmatic aspects, but also for

its cognitive ones. As we learn more, we understand how a fundamental

formulation takes effect through Internet and interactivity: from

a lower system, we can have the projection of a higher level. This

formulation means that it is possible, although physically located

within fixed three-dimensional spatio-temporal limits, to have ideas

about a space with more dimensions than our own, and to use, imagine

and, to some extent, understand it; even to design this multidimensional

space.

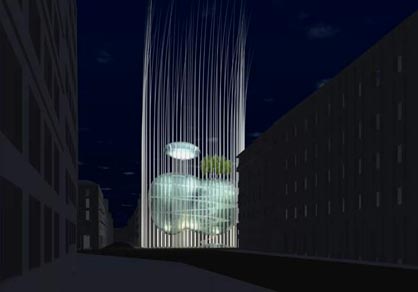

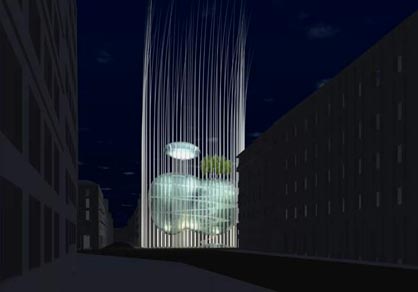

Makoto Sei Watanabe, Fiber Tower, Milan, 2004.

At

this point, I hope that it is now clear how three key questions can

be traversed by the concept of interactivity. First of all, through

the relationship with the world of contemporary communication and

a greater subjectivity of choices (and both these components have

an obvious implication with regard to the critical and political development

of singularity). Moreover, interactivity is a central factor in the

mental landscape of the new architectural research (through the absorption

of the dynamic models of information technology). Finally, interactivity

makes it possible to start to design and imagine spaces and architecture

that develop in not just three dimensions but which project upon themselves

the possibility of further dimensions through the process of jumping

and discontinuity.

|

|

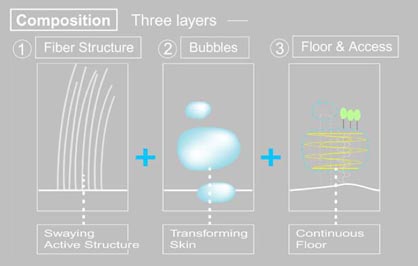

R&Sie..., Un Plug, reactive office building à

la Defense, Paris.

|

Diller+Scofidio, Cloud, Swiss Expo 2002.

|

|

The interactivity incorporated within the physical nature of buildings

means working at a new level of architectural complexity. But the

greatest challenge of all is not scientific (creating increasingly

mature mathematical models), nor technological (creating the physical

and electronic systems to enable levels of interactivity and sensibility

in buildings and settings). And neither is it even functional (understanding

how to make interactivity an element of research in the ‘crises'

and difficulties of contemporary society, rather than just a game

in the homes of the super rich). No, the true challenge is, as always,

of an aesthetic nature. Searching for an aesthetic (that is, a way

of seeing, interpreting and building the world of architecture) that

is deeply and necessarily interactive. It is here that the role of

the catalyst comes back into the picture.

Interactivity

is the chemical reagent, the catalyst of all these components. It

has, simultaneously, an ethical component and a political one, a technical

and a technological one, and it also has a fundamental aesthetic component

because it requires a revolution in sensing that pushes for a new

awareness of contemporariness.

Chaos Computer Club, Haus des Lehrers, Berlin, 2002.

Looking in an extremely summary manner at the change in the picture

of contemporary architecture, we can say that if the formula for the

Modern Movement was rightly Neue Sachlichkeit (New objectivity), the

formula for today cannot be other than New Subjectivity. And it is

interactivity that is the key to this new subjectivity. Transparency

used to be the aesthetic, and ethics the reason and technique of a

world that wanted rationally to tackle an advance in civilization

in terms of quality of life for the great masses of industrial workers.

Today, by contrast, interactivity constitutes a point of aggregation

for present-day considerations about an architecture that, having

gone beyond the objectivity of needs, can now tackle within its own

modifications the subjectivity of the desires of today's men and women.

Antonino Saggio

|

|

|