|

|

||||

| New Flatness: Surface

tension in digital Architecture * by Alicia Imperiale |

||||

[in italiano] |

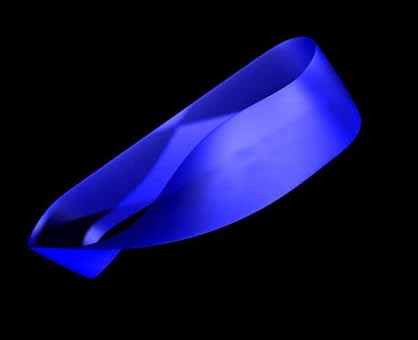

Skin rubbing at skin... Hides hiding hides hiding... If depth is but another surface, nothing is profound... nothing is profound. This does not mean that everything is simply superficial; to the contrary, in the absence of depth, everything becomes endlessly complex.(1) Slippery Surfaces The issue of flatness and surface has assumed a critical role in the last few decades. In broad cultural terms, there has been a movement away from dialectical relationships, from the opposition between surface and depth, in favor of an awareness of the oscillating and constantly changing movement from one into the other. In the context of architecture, the issue of "surface" is a recur-ring one. We see it in architectural discourse where in the last several years there has been a shift in emphasis to the articulation of topological surfaces in both architecture and landscape design. Many of the programs recently appropriated for use by architects have allowed this generation to work with remarkably complex curvatures and non-Euclidean shapes that would have been inconceivable without the use of the computer and sophisticated animation software. Programs such as Alias and Maya which are NURBS-based modeling systems, (Non-Uniform Rational Bézier Spline curves) allow the architects to simulate forces in complex and dynamically changing virtual environments that would then be proposed in built form. Through the use of algorithmic formulas the lines and surfaces are adjusted and recalculated continuously. This is an inherently more dynamic system: surfaces and objects are developed in a shifting relation to a surface.(2) Here the "surface" is more slippery than it might first appear. Questions regarding flatness, it turns out, are not superficial, but quite profound. In its very nature a surface is in an unstable condition. For where are its boundaries? What is its status? Is it structure or ornament, or both?  Klein Bottle. Illustration by Donald Baker. Depthlessness of Surface In the seminal book Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism,(3) Fredric Jameson investigates the lack of depth that characterizes postmodern culture, and the significant differences between the high-modernist and postmodern moment. A critical indicator of the postmodern, he asserts, is the reduction to a literal superficiality whereby all is reduced to flatness. Surfaces now exhibit a new depthlessness. He asserts that depth is replaced by surface, or by multiple surfaces. This depthlessness is not merely metaphorical - it is experienced literally and physically. Here Jameson sets the tone for the debate. Architecture, plastic, sculptural, voluptuous in its three-dimensionality is indeed reduced to pure surface. The absolute lack of depth signals the postmodern. But this is where the story begins, not where it ends. One cannot be neutral on this very point, and all architects must now position themselves in relation to the issue of surface. As a parallel, Mark C. Taylor discusses in his book Hiding (4), that everything comes down to a question of skin and bones. The skin is not a straightforward simple surface that cover-s our interiority. Rather, the skin is an organ, divided internally into differentiated and interpenetrating strata. It is a surface that is continuous in its depth and, like the Klein bottle, slips from outside to inside in a continuous surface. The model of the Möbius strip and the Klein bottle drive home to us the notion that dialectical distinctions, such as inside/outside, are emptied of their meaning.(5) Time frozen/form liberated? While one works on a design within the space of the computer, the form is constantly shifting, changing, according to varying parameters. Yet there may be a problem conceptually when an image is frozen and a static architecture built from that frozen frame. For the most part however, architects are relying on the fluid, interactive medium of working in the computer to convey this sense of continuous change. Given the fact that so many architects who work in this medium are influenced by the work of Gilles Deleuze, there is an emphasis on looking at the world as interconnected and smooth. Yet it is utterly inconsistent with this thinking to articulate a particular kind of form (or typology above all). However, there seems to be an uncanny link between the desire to make smooth, continuous space and the way a NURBS system works. It seems that the predominance of complex curved surfaces is linked to the use of animation software. What has evolved is a dialectic of the "blob versus the box". One should be cautious in making reductive statements that would equate good design with complex form, or for that matter to denounce sinuously curved architecture as merely a stylistic choice. It is not as simple as stating that there is an architecture of curved surfaces or an architecture of flat surfaces. In A Plea for Euclid (6), Bernard Cache regrounds the notion that topology (the development of surfaces) is actually incorporated within the system of Euclidean geometry. This is an important point, which comes at a critical moment. It allows for an architecture of continuity, whether composed of flat orthographic or curved surfaces. The emphasis in all of the work on continuity of surface, flow of space, and smoothness are not inevitably tied to the necessity of articulation in curved surfaces. The use of time-based animation software such Maya may be promulgating this bias, just as the program FormZ had emphasized a certain formal interpretation of the fold in the early 1990s. One must be critical enough to separate how work performs on a conceptual level, on the one hand, from an equivalency in its formal manifestation as developed through a certain instrumentality, on the other. Smooth exchange, flow, continuous surface - these are concepts that are ever-present in contemporary culture. They are issues that signal paradigmatic shifts of enormous import in the relationship between man and technology [8] - which appears more and more to be one of dissolving distinction.While one works on a design within the space of the computer, the form is constantly shifting, changing, according to varying parameters. Yet there may be a problem conceptually when an image is frozen and a static architecture built from that frozen frame. For the most part however, architects are relying on the fluid, interactive medium of working in the computer to convey this sense of continuous change. Given the fact that so many architects who work in this medium are influenced by the work of Gilles Deleuze, there is an emphasis on looking at the world as interconnected and smooth. Yet it is utterly inconsistent with this thinking to articulate a particular kind of form (or typology above all). However, there seems to be an uncanny link between the desire to make smooth, continuous space and the way a NURBS system works. It seems that the predominance of complex curved surfaces is linked to the use of animation software. What has evolved is a dialectic of the "blob versus the box".  Moebius Strib. Illustration by Donald Baker. One should be cautious in making reductive statements that would equate good design with complex form, or for that matter to denounce sinuously curved architecture as merely a stylistic choice. It is not as simple as stating that there is an architecture of curved surfaces or an architecture of flat surfaces. In A Plea for Euclid [7], Bernard Cache regrounds the notion that topology (the development of surfaces) is actually incorporated within the system of Euclidean geometry. This is an important point, which comes at a critical moment. It allows for an architecture of continuity, whether composed of flat orthographic or curved surfaces. The emphasis in all of the work on continuity of surface, flow of space, and smoothness are not inevitably tied to the necessity of articulation in curved surfaces. The use of time-based animation software such Maya may be promulgating this bias, just as the program FormZ had emphasized a certain formal interpretation of the fold in the early 1990s. One must be critical enough to separate how work performs on a conceptual level, on the one hand, from an equivalency in its formal manifestation as developed through a certain instrumentality, on the other. Smooth exchange, flow, continuous surface -these are concepts that are ever-present in contemporary culture. They are issues that signal paradigmatic shifts of enormous import in the relationship between man and technology (7) -which appears more and more to be one of dissolving distinction. |

[30aug00] |

||

| Alicia Imperiale Aliim@aol.com |

||||

| Notes

|

||||

|

(*) That this edited article was prepared for my

lecture in Dr. Prof. Berardo Secchi's course at the University of Venice (IAUV) on June

21, 2000. The text is excerpted from the book New

Flatness: Surface Tension in Digital Architecture, Birkhauser-Verlag, August 2000.

Forthcoming Italian edition, November 2000 by Testo & Immagine, Antonino Saggio,

Series Editor. Also, a slightly longer version of this article will be published this fall

in the magazine "Il Progetto". (1) Mark C. Taylor, Hiding, The University of Chicago Press, 1997. (2) For a very clear and concise description of NURBS-based programs and the implication of these time-based systems on architecture see Greg Lynn's Animate Form, Princeton Architectural Press, 1999. This section is also based on an interview by the author with Cory Clarke. See http://www.webreference.com/3d/lesson37 for introduction to NURBS. For a survey of recent work in this area see "Domus" 822, January 2000. (3) Fredric Jameson, "Postmodernism, or, The cultural logic of late capitalism", Duke University Press, 1991. (4) Taylor. (5) The discussion of bodies arises from the Deleuzian discussion of the layering and folding of matter that forms all bodies as discussed in the texts: Gilles Deleuze, "The Fold -- Leibniz and the Baroque", University of Minnesota Press, 1993 and Bernard Cache, Earth Moves: The Furnishing of Territories, MIT Press, 1995. The mathematical models of the Möbius strip (a one-sided surface that is constructed from a rectangle by holding one end fixed, rotating the opposite end through 180 degrees, and joining it to the first end) and the Klein bottle (a one-sided surface that is formed by passing the narrow end of a tapered tube through the side of the tube and flaring this end out to join the other end) are offered as spatial models that might be incorporated in the making of a continuous architecture. (6) Bernard Cache, excerpted from, "A Plea for Euclid" on this site in Extended Play: "One should not think of Euclidean geometry as cubes opposed to the free interlacing of topology. On the contrary, it is only when variable curvature is involved that we start getting the real flavor of Euclid. Willingly or not, architects measure things, and this implies a metric... Only by mastering the metrics, can we make people forget Euclid... Many unexpected figures will then enable us to incarnate complex topologies in Euclidean space. We have only caught a whiff, we haven't really tasted it yet!" (7) Allucquère Rosanne Stone, "Electronic Culture: Technology and Visual Representation", edited by Timothy Druckrey, Aperture Foundation, Inc., New York 1996. |

|||

|

||||

| laboratorio

|

||||