|

|

| home > files |

| Calculated

Ambiguity Elena Carlini and Pietro Valle |

| [in italiano] | In

the last fifteen years, London architect Tony Fretton has completed

a series of buildings that are particularly significant for their construction

of public spaces, for the not-declared use of architectural precedents

and for a conceptual position akin to some contemporary art practices.

Fretton's built works—houses, art galleries, alternative religious communities—are

adaptations of existing structures or insertions of new spaces in layered

contemporary contexts. At first glance, they strike for their ordinary

and almost 'invisible' presence but gradually they reveal subtle compositional

shifts that promote multiple relations among different spaces and a

not prescriptive use for them. Fretton's buildings and projects do not

declare beliefs or theoretical manifestoes, they employ spurious forms

that cannot be related to already known paradigms and rather absorb

elements from their sites in an oblique and detached manner. Having

nothing to say openly, Fretton's spaces raise questions on their

meaning and use. This ambiguity is not casual but part of a deliberate

strategy to promote an imaginative use of the spaces by their users

and a dialogic architecture that employs none of the forced ideologies

that have been associated with social engagement in the last decades. |

[03jul2003] | ||

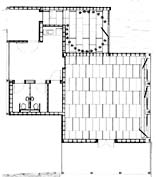

Quay Centre for the Arts. Plan. |

Fretton

employs various spatial modes to promote his calculated ambiguity.

His research does not focus on innovative form nor on single spectacular

elements but indeed on the multiplication of the relations and

the thresholds among spaces. In many schemes, Fretton places

multiple visual channels and paths between interior and exterior employing

openings that orient space in a different way according to the direction

one crosses it. The rooms of Lisson Gallery 2 are projected in the street

and, at the same time, they reflect it in their large windows. The openings

are continuous ad undivided but they are also adapted to the levels

of the existing school complex facing the gallery that is brought into

a dialogue with its spaces. The window shop thus becomes an apparatus

that creates a multidirectional trafficking between the interior

and the street reversing the roles of exhibition space and the city.

In the design for the Hotel ProForma in the Danish city of Ørestad,

The ground floor is also treated as a public room with weak transitions

among the various spaces so to make them partake of the exterior. The

plaza facing the hotel is extended horizontally but also doubled in

height through a terrace/canopy that reaches the ground by folding on

one corner. In the competition entry for the Laban Dance Center in Deptford,

all the main spaces face a courtyard marked by large openings. This

central space penetrates the interior and becomes an indoor street

and an outdoor room at the same time. |

|||

Holton Lee, Faith House. Porch. Photo by Hélène Binet. |

Holton Lee, Faith House. Exterior. Photo by Hélène Binet. Another strategy employed by Fretton to mark relations among differences is an apparent room specialization. As in the traditional Arts and Crafts house, the interiors are composed of rooms with different characters placed side by side and tied by multiple openings. To such a scheme, Fretton adds a more archaic theme coming from a reading of medieval and Elizabethan houses: the lack of serving spaces such as corridors or hallways. In his interiors, you move through the rooms and each o them serves both as circulation and a stable place. Spatial differentiation, once marking a zoning of different uses, is now used just to characterize the rooms but, at the same time, is denied by the transition through them and by a functional indeterminacy that allows multiple uses. An interior by Fretton can be read both as a single environment articulated by different sub-spaces and as a sum of adjacent worlds that promote a continuous sense of discovery when one passes from one to the other. There is a possible city analogy in these interiors: moving through the rooms reminds one of an urban derìve through different streets and buildings. |

Holton Lee, Faith House. Plan. |

||

| This

continuous drifting (physical and imagined) is also reinforced by the

lack of hierarchy with ultimate starting and arrival points. The spatial

contiguity can be organized in a linear sequence as in the Quay Arts

Centre, with a vertical arrangement as in the Groningen house or in

a multidirectional 'field' matrix as in the Centre for Visual Arts at

Sway or in the Faith House at Holton Lee. The key for relating discontinuous

spaces is sectional and light manipulation handed through different

horizontal and vertical openings. As in a John Soane interior, Sway

is composed of rooms each with a different skylight: the building becomes

a composite landscape that, even if not open to the exterior,

allows to perceive individual places through height and light

intensity. The house in Chelsea wraps rooms with different heights in

a unitary envelope. They are related with multiple stairs and the whole

scheme reminds of Loos raumplan where complexity is imploded within

an abstract and undifferentiated container. The plan of the Faith House

at Holton Lee joins along two central orthogonal walls a series of centrifugal

spaces, each oriented towards a different vista. |

Holton Lee, Faith House. Quiet Room. Photo by Hélène Binet. |

|||

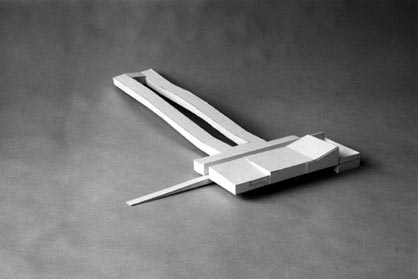

Holy Island, Arran. Retreat center plan and sections. |

Holy Island, Arran. Retreat center model. Photo by Tony Fretton. The apparent functionality and the abstract language employed by Fretton are contradicted by the aforementioned awkward room contiguity that denies traditional rationalist strategies such as sequences, proportions and division between serving and served spaces. Fretton rereads an empirical tradition that is profoundly British and is accustomed to join differences without a preestablished general scheme. An informal/picturesque landscape sensibility helps him both in articulating interiors and in displacing sparse objects in his countryside schemes such as Holton Lee, Sway and the Buddhist religious center at Holy Island. Temporal sequences experienced by walking along non-linear paths, distant views and a few material affinities with rural structures tie new and existing buildings. The various artist studios, community rooms and meditation centers aim at appearing as archetypical structures set within nature but they are also aware of playing a representational role: halfway between new settlements and follies, they remind that an informal landscape is also an artifice and is based on fictional construction. The portico of the Faith House at Holton Lee thus becomes an abstraction in wood of a Greek temple while the interior encloses a miniature Stonehenge made of tree trunks. The two retreat centers at Holy Island stretch a monastic courtyard type along a hillside and have the room wings softly deformed by following the existing slope. |

|||

House in Chelsea, London. Exterior. Photo by Hélène Binet.  House in Chelsea, London. Main lounge. Photo by Hélène Binet. |

The

aforementioned examples show that Fretton is interested in a projective

reading of his buildings and their impact on the site. For him,

architecture internalizes many suggestions from an existing environment

but it does not quote them openly and instead seems interested in transformative

processes through which spurious linguistic fragments are adapted to

different ends. In his search for an imaginative participation of the

inhabitants to the creation of space, Fretton avoids absolute models

and provides instead ambiguous hints to appropriate. In doing so, he

is interested in the invisible fabric of anonymous structures

where his project are located: the continuous rows of buildings where

no single entity emerges (the industrial complex where the Centre for

Visual Arts at Sway is located), the historic townhouses (the house

in Chelsea), the commercial storefronts (Lisson 2) or the farm groupings

(Sway and Holton Lee) where new structures can be added without altering

the general disorder that governs them. |

|||

| The

fact that these buildings form an anonymous contemporary vernacular,

matter to Fretton more as a process than as a final form. In their transformations,

he recognizes an additive and estranged memory that has no interest

in fixing analogous forms but acts as a bricoleur that keeps

on shifting his operational procedures. The interest in the 'situationist'

deformation of language in specific contexts and the search for public

interaction align Fretton's practice with the experimentations of many

Conceptual and Post-Minimalist artists active since the 1970s (to quote

just one example, Lisson 2 is one of the few contemporary buildings

that acknowledges Dan Graham's research on public space through transparency

and reflection). Fretton knows well these movements thanks to his contacts

with the arts scene and the design of many exhibition spaces. He has

been able to translate their processual experimentation into architecture

without employing a recognizable language. While many architects have

borrowed and thematized formalist themes from the visual arts (think

of the Neo-Minimalist fashion), Fretton acknowledges the continuous

rethinking of relational strategies as the true value of recent

art and ties this open conceptual search to his interest in public interaction

and in the transformation of existing places. |

House in Groningen. Street view. Photo by Christian Richters.  House in Groningen. Plan and sections. |

|||

| In

his working method there is also a form of resistance against the too

fast consumption of motifs, ideas and images that characterizes many

international architectural practices. Fretton understand that, within

the elusiveness of his architecture, there is an open territory of latent

possibilities to re-imagine the built environment without being

tied to an inclusive formula. The ghost presence of the streets he mentions

in his description of Lisson 1 is just one example of the imaginative

richness he tries to maintain open in his architecture. In this exploration,

Fretton is one of the few architects that have acknowledged the extraordinary

contribution of the late Robin Evans on architectural projections. In

his analysis of the role of geometry in design, Evans pointed out that

projections are not just a passive representational tool but become

an active system to explore reality and a vehicle for ideas between

culture, space and materiality. He noticed that, within architectural

codes that seem concluded, there is a relational surplus where

projections play an active role in conveying additional layers of signification.

(1) Fretton understands this possibility of open relations and tries

to address them to the users of his spaces without prescriptions. Evans investigations and Fretton's project therefore take the responsibility to reiterate architecture's complexity through its unfinished projective nature. Their work on open communication and the social relation this provokes is particularly significant in a moment where architecture becomes just fast consumption of one-dimensional images. While the market has appropriated many tools of the so called experimental movements in architecture, the silent construction of a radicalness without avant-garde, such as that proposed by Fretton, could constitute a responsible approach to architecture. Elena Carlini, Pietro Valle carlinivalle@everyday.com |

||||

|

NOTE: |

||||