|

|

| home > files |

| Tony

Fretton interview Elena Carlini and Pietro Valle |

| [in italiano] | ELENA

CARLINI AND PIETRO VALLE. In some of the collective spaces of your buildings

and projects (we think of the Lisson Gallery 2, the Hotel ProForma lobby

and the courtyard in the Laban Dance Center) there are many 'open’ thresholds

and no ultimate boundaries. These displaced edges (obtained through

views, framings and reflections) promote a complex public interface.

What notion of public space is at work here? |

[03jul2003] | ||

| TONY

FRETTON. I should like to say place instead of space. |

||||

Public

places for which I accept responsibility as designer, which I make from

other spaces I have experienced. These can be successful formal public

spaces, natural spaces where people experience a relation as human beings

with the animal, vegetable and mineral world and cosmos, interiors which

carry powerful messages of social ritual, rooms which people have made

their own. Lisson Gallery 2, London. View from the street. Photo by Chris Steele-Perkins. I rework this material without bringing it to a single conclusion, trying for a calculated ambiguity in the hope that what I make will be open to physical and imaginative occupation by others. In fact this is how all buildings work. Hardly anyone knows the designers name or intentions; they just make sense of the objects they find. And with highly ambiguous objects like Stonehenge, the lack of information on intention and use only stimulates a more imaginative engagement. |

||||

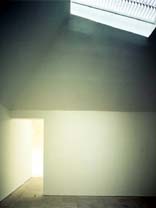

| You

have designed many buildings for the contemporary arts (The two Lisson

galleries, The Quay Arts Centre in the Isle of Wight, The Center for

Visual Arts at Sway, the proposals for a gallery in Hoxton and for the

Open Hand Studios at Reading). All of them seem to present a tension

between specific spaces and the accepted ‘neutrality' of the 'white

cube'. What notion of the exhibition space do you have developed through

these successive projects? |

||||

Lisson Gallery 1, Londra. Back gallery. Photo by Lorenzo Elbaz.  Lisson Gallery 1, Londra. Axonometric. |

Galleries

have had their own intentional language of neutrality for the last 35

years let's say, and that they are always restlessly trying to change.

That is why Saatchi recently put all that Brit-Art into the former County

Hall, a building that is early 20th century beaux-arts. I always make art space in which the art and not the architecture is the most visible part. The white neutrality you name, I use as a sort of ghost of real life. The geometries in the first building we made for the Lisson in 1986 were those of the site and surrounding streets. Visitors came into the gallery through a door of etched glass that reduced but did not cut off the view of the street. The streets gave way to a ghost of their forms, which was also the white neutrality of international art space. So the gallery had a sense of place while being a background to the art. Many of your projects present contiguous rooms of different character and with multiple openings that completely obliterate the difference between serving and served spaces. You move through the rooms, either linearly (in the Quay Arts Centre), in multiple 'field' configurations (at Holton Lee and in the Centre for Visual Arts at Sway) or vertically (the houses in Chelsea and Groningen). The interior becomes a complex landscape with adjacent options that articulate the character of a building. Do you find this an acceptable reading of your designs and, if so, can you talk about it? |

|||

| Yes,

I aim to make spaces of different characters related to their outlook,

use and social function that combine as a larger social entity. There

are times when the situation and construction lead to this being the

continuous space that came with modernism. But it can also be the type

of spatial arrangement of a palazzo or domestic house grown large. The picture that emerges for me in these spaces is that now more than ever, we as human beings need to acknowledge mutuality, while retaining our freedom to enjoy our differences. I am looking at the relation between well-constructed creative and intelligent regulation and the space for freedom of expression it can provide. |

||||

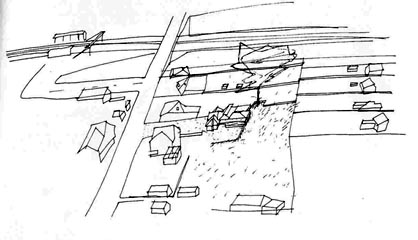

Hotel ProForma, Ørestad. Model views. Photo by David Grandorge. |

Talking

about landscape, there seems to be a very layered reading of

the sites where your projects are located, no matter if they are existing

structures to be modified, urban or rural areas. You seem to respond

to these sites with apparently simple forms that are instead composed

of complex spaces. What are your ideas about contextuality? Can they

possibly be linked to a very English notion of landscape coming

from an informal and anti-hierarchical tradition? Maybe this is our

perception but we seem to detect a notion of order and rationality that

is very different from the one we are accustomed in Italy... |

|||

| Now

that I have worked in Continental Europe for a while I see that British

culture is empirical while European thought works by principle. Broadly, things are only satisfactory to British people if they operate well in life. This gives us the ability to respond to situations and physical contexts in a very imaginative way. But it also leads to conservatism and inaction. The European tradition provides everyday models of intellectual order and planning which are not available to me in Britain. This is something I am working out not only in my buildings but the Masters program of my department at TU Delft. Urban and rural sites seem to provoke different responses in your projects. While in the urban sites you seem to adapt accepted types (like the traditional townhouse), in the rural projects you often propose settlements with different structures dialoguing at a distance. In the city, complexity is interiorized; in the countryside, there are many simple structures. Are these two faces of the same approach? Well there is often more space in the country locations, so I have greater freedom to not define places architecturally but manage them somehow so that they are more anarchic and open to interpretation. This is a very difficult thing to achieve and quite often I do not succeed. If you only make minimal changes in the surroundings, people often change them and everything is lost. |

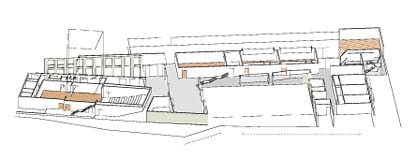

Hotel ProForma, Ørestad. Ground floor plan. |

|||

Laban Dance Center, Deptford. Ground floor axonometric. Success requires more intervention than you would first think. Alvaro Siza's swimming pool on the beach at Leça de Palmeira is incredibly good at this. Things change around it and it reflects them somehow. Dan Graham, too is a great example. I have seen his mirror pavilions photographed in several different locations, and have experienced them in London and New York many times. They are unashamedly pieces of art in themselves and yet highly social and generous to their setting, however it changes. |

||||

Centre for Visual Arts, Sway. Ground floor. |

In

your lectures and publications, you talk about the social responsibility

of the architect in responding realistically to the demands posed by

specific commissions. By looking at your projects, you seem to articulate

these demands in a complex way, never giving a unitary answer. Is this

a form of critique of accepted ways of handling functional programs?

If so, how does sociality plays a role here? I hope I have gone some way to answering this in my previous replies. But to say a little more: great design has always been about enabling people and providing a specific type of certainty. The certainty I mean is artistic certainty, which of course is not certainty at all but confidence and good-natured belief. |

|||

| What

role do materiality and tectonics play in your projects? Do they emerge

at the beginning of a project or do they develop gradually? They are very much an outcome of other interests. I do study these aspects in other buildings, and, as an office, we are careful and risk averse in construction.  Centre for Visual Arts, Sway. Sketch. But it only takes a short time to see that constructional decisions are culturally determined, so the conversation we have about procurement, cost, delivery and completion are carried out in similar terms to my discussion here in this interview. At Holton Lee and Holy Island you try to define a new kind of non denominational religious community with very interesting spatial solutions. How do 'community' and 'religion' interplay here? Well, the Holy Island competition was in a for Tibetan Buddhist community with a very powerful system of beliefs and rituals. Faith House at Holton Lee is for a community that is genuinely non-denominational. And in the next few weeks we may probably be asked to design a Quaker meetinghouse. Since I am not a follower of any of those paths I have had to establish the approaches through which I could work on these projects. One is as an instinctual existentialist, interested in what it means to be a human being in relation to the natural world. Another is an instinctual attraction to classical Greek myth and the way it was treated by Aeschylus. Here, an artist is contact with great material and understands his role, but also his frailty. A further line is through Sigurd Lewerentz, especially his landscape work in the Woodland Cemetery in Stockholm. The style of the arrangement of trees, hills and objects points to a pagan era before Christianity. But of this is a fiction, just as it is when Kahn implies that his buildings point to our classicism. In situations like this you cannot be ironic or detached, you have to deal with and see value in beliefs, even if they are not the ones you share. |

Centre for Visual Arts, Sway. Gallery 3. Photo by Lorenzo Elbaz.  Centre for Visual Arts, Sway. Gallery 1. Photo by Lorenzo Elbaz.  Centre for Visual Arts, Sway. Gallery 2. Photo by Lorenzo Elbaz. |

|||

|

>

CARLINI E VALLE: CALCULATED AMBIGUITY |

||||